Ben Thompson of Stratechery, a VIP member on Notorious, recently wrote a post on Tech and Antitrust that is absolutely fascinating on a lot of levels. Although that post is open to the public, if you’re not a subscriber to his Daily Update, I strongly recommend it.

Ben looks at antitrust actions by the European Union as well as word that the US Dept. of Justice is looking at Big Tech (Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, etc.) to see if there are competitive issues in technology. I’m obviously not going to review the entire post, so go read the whole thing.

But I wanted to look at something in real estate using Ben’s framework as an analytical tool. It’s actually kind of fascinating.

Basically, after reading that post, I’m wondering if the DOJ antitrust investigation into real estate, which currently appears to be looking only at the MLS and the system of cooperation and compensation, might not also involve an investigation into Zillow and potentially force a breakup of Zillow Group.

Let’s get into it.

Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory

We have to begin with Ben’s incredibly insightful take on Web 2.0 technology companies that he calls Aggregation Theory. Again, read the whole thing, but the big concept/takeaway is this:

This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be commoditized leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

The result is the shift in value predicted by the Conservation of Attractive Profits. Previous incumbents, such as newspapers, book publishers, networks, taxi companies, and hoteliers, all of whom integrated backwards, lose value in favor of aggregators who aggregate modularized suppliers — which they often don’t pay for — to consumers/users with whom they have an exclusive relationship at scale.

He goes on to look at Google, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Uber, AirBnB and others under Aggregation Theory.

I think it’s exactly correct. I’ve been thinking along similar veins for years under the term “Home Depot Effect” because I can’t remember the name of the contractor who installed my windows, but I do remember that I bought them from Home Depot… so as far as I’m concerned, Home Depot installed my windows.

The application to real estate, particularly to the portal wars of the past decade or so, is obvious. The real estate industry used to be one where, to quote Ben (while interjecting), one where “distributors [brokerages/companies] in all of these industries integrated backwards into supply [agents and listings]… a world where transactions are costly owning the supplier relationship [the MLS] provides significantly more leverage.”

The portal wars began the process of transformation, and Aggregation Theory perfectly describes what happened: aggregating modular “supply” (i.e., listings and agents) and selling that supply to consumers who have an exclusive relationship at scale.

That last part is important, since real estate brokers and agents love to think they have a corner on consumer relationships: sphere, farm, etc. etc. But not at scale. Brokers and agents still have great local relationships but not what an Aggregation Theory requires.

Regulation and Tech: Aggregation

Now, Ben discussed how government regulation of these aggregators are a different game than the traditional 20th century antitrust actions, because the market power of the aggregators are directly related to and reliant on their relationship with consumers. People go to Google because they like it; if they didn’t, they could easily use any other search engine. The same for Facebook and Amazon and Netflix and whatever else. But because those companies have mastered web and mobile user experience, and offer all kinds of benefits and goodies to consumers, consumers flock there and start the network effect which brings suppliers/sellers there.

In discussing various antitrust actions and investigations by the government, though, Ben writes this about Facebook:

Facebook: There are certainly plenty of reasons to be upset with Facebook when it comes to issues of privacy, but the company has not done anything illegal from an antitrust perspective.

I am, to be clear, distinguishing anti-competitive behavior from anti-competitive mergers. I have made the case as to why Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram was so problematic, and this is the area that needs the most urgent attention from anyone who cares about competition. The single best way to maintain a dominant position in a market as dynamic as technology is to use the outsized profits that come from winning in one market to buy the winner in another; it follows, then, that the best way to spur competition in the long run is to force companies to compete with new entrants, not buy them out. [Emphasis added]

As I understand Ben here, he’s saying that Facebook does nothing that is anticompetitive… but its acquisition of Instagram, which eliminated a potential competitor, was problematic. If Instagram were a separate company today, it might be a fierce competitor for advertising dollars that are flowing into Facebook now.

So, the remedy to the Facebook competitive problem is forced divestiture:

Facebook: Facebook, fascinatingly enough, given its lack of anticompetitive behavior, has the most obvious remedy: break apart Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. I do believe this would be beneficial for competition: Instagram being an independent company would not only add another competitor for digital advertising, but would also make other companies like Snapchat more competitive by virtue of forcing advertisers to diversify. Again, though, this is more about a failure in merger review.

That sets the stage for our discussion on Zillow. But do read the rest of Ben’s post; it’s really, really good and fascinating on multiple levels.

Zillow and Antitrust

We already know that Zillow survived antitrust review of all of its acquisitions, Trulia being the big one, but MLOA and StreetEasy and others also survived review. Because none of those had dominant market power, as defined by the government. It isn’t even clear that the combined Zillow Group entity has dominant market power in terms of leads; Realtor.com is still making tons of money, and Redfin makes a boatload from its Partner Agents program, and there are literally dozens if not hundreds of smaller companies that provide all kinds of lead generation tools, platforms, etc. etc. Brokers and agents supply leads (aka, referrals) every single day.

The interesting question, however, is whether Zillow’s entry into a new and related market to its core aggregation should or could be analyzed for competitive effects.

Specifically, I speak of Zillow Offers and the massive pivot of the company as 2019 began with the King of Gondor Rich Barton returning to the CEO position. I’m not going to go into too much detail about that since I wrote a full 70-page Red Dot on it. But by now, we know that Zillow has pivoted and is pivoting.

In a way, that’s the antithesis of antitrust. Zillow saw what Opendoor and Offerpad and others were doing, realized that’s a cool business, and jumped in. I don’t have a ton of data from the field on this, and anecdotes are completely scattered and mixed, but the general feeling in the industry is that Zillow is “undercutting” both Opendoor and Offerpad by paying more for houses through Zillow Offers. The data I do have shows that Zillow’s spread is a mere 1.4% (the price at which it sold the house vs. the price at which it bought that house). That’s “savings” for consumers, isn’t it? Which is pretty much the hallmark of competitive markets?

Except that the limited data I do have [VIP post] on Opendoor’s activities shows that Opendoor’s spread was an even lower 0.9%. So why is this an issue?

Are Other iBuyers Competitive Against Zillow?

Again, solid information is really really hard to come by here, but let me cite two things I do know from the two public companies involved in iBuying: Zillow and Redfin.

First, for FY 2018, Zillow showed a 0.6% gross profit margin from its Homes segment. Redfin, in contrast, showed a loss of 4.3% from Redfin Now. I wrote about this in the April Red Dot:

On the one hand, Redfin Now turned in a surprisingly robust result. The Properties segment turned in $46.6 million in revenues for 2018, up 350% from the $10.4 million it posted in 2017. Seeing as how Zillow Homes only posted $52.4 million in revenues for 2018, what it says is that Redfin quietly and quite beneath the radar has built an iBuyer business that is as large as Zillow’s.

So that part’s great. But on the other hand… here’s Chris Nielsen from the earnings call:

For our properties segment, cost of revenue includes the purchase price, capitalized improvements, selling costs and home maintenance expenses. In the fourth quarter, properties gross margin of minus 4.3% was down from 2.4% in the fourth quarter of 2017, primarily due to a 490 basis point increase in the cost of properties, a 150 basis point increase in personnel costs, including stock-based compensation due to increased headcount and an 80 basis point increase in transaction bonuses, each as a percentage of revenue. [Emphasis added]

This is a problem. And I’m going to make a bigger deal of this than perhaps others might because it goes to the heart of Redfin’s claim of superiority: execution.

Second, we have this from Spencer Rascoff from the Q1 earnings call last year. The following comes from the June 2018 Red Dot:

What fewer people recognize is the data advantage that Zillow has from all this website traffic. Thankfully, Spencer Rascoff, Zillow’s CEO, lays it all out for us:

So, I guess the way that we will benefit from the demand side of the funnel is by selling these homes quickly and at a high price or higher price than if we didn’t have access to the demand. We will also benefit from having the demand side of the marketplace by being a smarter bidder on the homes that we are buying. [Emphasis added]

Could this be one reason why Zillow apparently turns a profit while Redfin does not? The aggregation of consumers leads to data advantages which leads to competitive advantages in bidding? Now, to be fair, in the most recent quarterly earnings call, Zillow lost money on Homes… but it’s still making gross margins, albeit tiny. I don’t know that Opendoor and Redfin are.

Plus, Zillow executives from Spencer to Jeremy Wacksman to Rich Barton have all mentioned how their marketing costs for Zillow Offers is essentially zero. Because the consumers are already all on Zillow, so putting a button to request an offer in front of them, or marketing homes that Zillow owns to buyers, is easy as pie. Actually, baking a pie is hard, so I don’t know where that saying comes from. It’s really easy for Zillow, in a way that it isn’t easy for everybody else.

Zillow and Aggregation Theory

At the same time, it isn’t as if Zillow has some sort of stranglehold on consumers. Like Google might say, “competition is a click away.” If you listen to people like Eric Stegemann of Tribus, it’s easy to beat Zillow! He’s helping brokers do it all the time! Or so he says.

Zillow has power because consumers go to Zillow. They like Zillow. They like the Zillow App. And like all the other Aggregation Theory companies, Zillow knows that it must provide the best user experience for consumers, or die.

It’s using that relationship with consumers at scale to do other things, and Zillow has always tried other things, as would any company anywhere of any size. It got into rentals. It got into mortgage leads, until Zillow bought MLOA at least. It does transaction platforms (Dotloop) and data technology (Bridge) and so on and so forth. Why not iBuyer?

And if Zillow has a competitive advantage in iBuyer because it has aggregated consumers, well, good for them, right?

Unlike Facebook, which bought a potential competitive threat (Instagram), Zillow simply went into the market and competed against other iBuyers. There is no FTC review. No DOJ antitrust review of the proposed merger. It is just competing for business, like we want companies to do.

So what’s the problem?

The problem is that it isn’t clear that any other iBuyer could possibly compete against Zillow. Everyone can get cash; everyone can get a really disciplined ground game of contractors, managers, buyers, etc.; and everyone can invest in technology, in engineers and data scientists and the like. The one thing that no one else can get without somehow climbing a near-insurmountable barrier is traffic: aggregation of demand. That relationship with the consumer at scale is the most valuable asset that Zillow has, and no one else can actually get that in any reasonable timeframe and expense to make even trying worthwhile.

If I’m a regulator looking hard at the industry, I might want to take a look-see at this new and fascinating sub-industry of institutional real estate that is rising before our eyes.

Now, I don’t know that there’s anything they can actually do about it. After all, Zillow hasn’t bought a competitor. It hasn’t refused to take ads from competitors like Redfin and Opendoor. It merely has this massive competitive advantage in traffic, and is leveraging that into a new business, and bringing more competition into that business.

And yet….

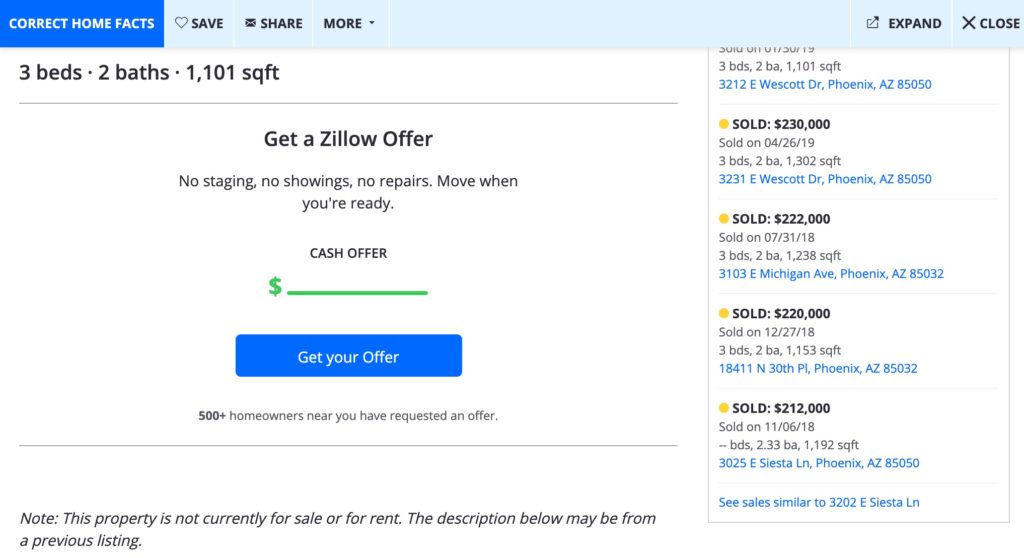

When Ben Thompson talks about how Google favors YouTube results in search over any competitor videos (like Vimeo), and that the remedy is to force Google to be evenhanded and fair… I can’t help but think about the giant “Get a Zillow Offer” ad on properties not for sale in Phoenix.

Could the government force Zillow to show similar “Get an Offer” button from Opendoor, Offerpad, Redfin, and whoever else? I don’t know how they have the power to do that in the United States. Maybe they do. I just don’t know.

Or could the government break up Zillow into its major business units, and force each to compete on its own strengths and weaknesses? There is some precedence of government action there (e.g., AT&T), but that isn’t likely until we see real dominance (like 50+%). It’s not clear to me that competitors could survive that long.

For now, the government appears to be focused on 20th century business models and 20th century problems, like cooperating compensation and availability of MLS data. But with how fast things move, I wouldn’t be surprised if they started thinking about 21st century business models based on Aggregation Theory and 21st century problems with competition.

Or maybe I would….

Your thoughts are, as always, welcome.

-rsh

4 thoughts on “Zillow and Antitrust? Reflections on Stratechery’s Tech and Antitrust”

“But because those companies have mastered web and mobile user experience, and offer all kinds of benefits and goodies to consumers, consumers flock there…”

This is my problem with the “regulate Silicon Valley!” argument.

The only way they keep the throne is by *earning* consumers. Continuously.

Similarly, this from the Stratechery article:

“the more consumers use a search engine, the more attractive it becomes to advertisers. The profits generated can then be used to attract even more consumers.”

That literally describes every business known to man. “Do a good job, earn consumer dollars which you can reinvest to earn more consumer dollars”.

These are all good things for us. Why are we complaining?

It is hard to disagree with the fact that consumers will “pivot” to those organizations who are successful at doing one critical thing.. Converting things in their lives that now represent “chaos into order.”

This is, with only a few exceptions, a good thing for the consumer is almost always a threat for whomever it is that has been “organized.” So the resistance should be no surprise, it should actually be expected.

In real estate the archaic architecture and structure of the historically B2B MLS, and the chaos that created by when suddenly the MLS became the B2C face of the industry, was significant. With at one time more than 800 MLSs, and now 14 years after Trulia was created we still have some 610 MLSs (insane), absent the chaos the portals organized, searching for properties nationwide was impossible. But R.com, and Trulia and eventually Zillow changed all that. And to be clear, that change was met with huge “headwinds” from the industry.

And so, the industry began its revolt.

It was no secret that the real estate industry preferred to keep the consumer out, the data captivated in their B2B MLS environment. And then the portals, empowered by the consumer’s desire for “order”, stepped in and fixed the problem that had been perpetuated by the disparate, fragmented MLS industry. And what is wrong with doing that? I think the only crime committed by the Trulia and Zillow portals was being too consumer-first focused. And as we all know, while that may be controversial, that is in no way can be considered a crime.

Further, the only real government intervention or examination to date in this industry has been focused on the core operating practices of once again, the failed MLS industry. The MLS, as a supposed industry “utility”, has been accused and sued by both the DOJ and the FTC for anti-competitive practices, and now is being investigated for price fixing and other rather serious alleged violations of the law.

When is enough, enough for the MLS? And what a reoccurring mess the MLS represents that the brokerage industry really needs to clean up soon, as in like now.

Now enter the iBuyer model. And once again we see a company like Zillow being the consumer-first company that it is and this time essentially providing a viable alternative to the traditional brokerage processes. That’s right, Zillow and the other iBuyers are providing the consumer with an alternative to the antiquated processes used by most all traditional brokerages. And yes, to be clear, those traditional brokerages in the eyes of the consumer include; eXP, Compass, KW, the Indies, all of the franchises and even Redfin.

So now Zillow offers something different and the consumer has the option to apply a portion of their equity to essentially avoid using a traditional brokerage process to sell and buy real estate. No harm. No foul. All good.

Good for the consumer, they love choice, but not so good for the historically change-resistant residential real estate brokerage industry. The question is, what will it take for this industry to realize that “the taxi cab medallions” have no value any longer?

“When someone you have done business agrees now to take less and pay more just to avoid using your services, the trend cannot be a good thing.” Think about it.

And so goes the journey of other similar companies and industries as progressive change confronts tradition. Those companies include; Google, Zillow, Facebook, LinkedIN, Spotify, Uber, Netflix, Amazon are all in the same place and as far as I am concerned they have all participated in improving chaotic things and have succeeded in serving the consumer well.

So I guess what we are really seeing here is that those that apply a consumer-first strategy are a threat to those that don’t. And as far as I am concerned, those that seek to protect the rights of the consumer, to enhance a consumer experience, should be cheered on by the consumer for their efforts. It seems to me that those who ave the consumer’s best interest as their mandate will recognize these changes as positive. Seems to me to be “that plain and that it should be that simple.”

But then again, I have been wrong in making such industry observations many, many times before.

” The question is, what will it take for this industry to realize that “the taxi cab medallions” have no value any longer?”

Woot, and double woot! (dances around pointing at this comment)

Comments are closed.