[Editor’s Note: PadSplit’s Atticus LeBlanc was the guest on Episode 4 of The Blueprint Sessions. This is the accompanying essay, originally published as a members-only article for members of the GEM.]

Co-opting Inventory

Housing is simply not affordable for most Americans, whether they are renting or trying to buy. We’ve known this for many years. But now it’s worse, far worse. That’s as clear as day.

Glenn Kelman painted a damning tale of the attainability of homeownership in a tweetstorm, which was covered by Inman.

Some of his more salient points:

- There are now more Realtors than listings.

- Inventory is down 37% year over year to a record low. The typical home sells in 17 days, a record low. Home prices are up a record amount, 24% year over year, to a record high. And still homes sell on average for 1.7% higher than the asking price, another record.

- In 2020, new-construction permits were *down* 13% in DC and New York, 40% in LA, 48% in Chicago, 50% in Seattle, 79% in San Francisco. Permits were *up* 25% in Miami, 56% in Vegas, 96% in Greenville, 122% in Detroit, 246% in Knoxville.

- Lumber prices are up 300%.

- It’s not just income that’s k-shaped, but mobility. 90% of people earning $100,000+ per year expect to be able to work virtually, compared to 10% of those earning $40,000 or less per year. The folks who need low-cost housing the most have the least flexibility to move.

There’s simply no inventory though it is starting to uptick:

On the rental side, state-owned housing is one way to keep costs down because there is no investor hurdle rate (aka 15% IRR) to meet at an exit.

Nate Berg writes for Fast Company that in Berlin, “state-owned housing companies own and manage more than 325,000 units of housing across the city,” 17% of rentals. But that’s an aberration.

Meanwhile, Berg continues: “The New York City Housing Authority has the largest public housing stock of any U.S. city, but it still only owns about 170,000 housing units—accommodating just 5% of the city’s roughly 3 million households.”

The U.S. federal government remains the primary funder of affordable housing throughLow Income Housing Tax Credits given to developers, and rental subsidies, formerly known as Section 8 vouchers, given to renters. Having stopped building public housing projects in the 1960s and then passing a ’90s-era law that prevents it from building more, expecting the government to magically save the day on the supply side is unrealistic, certainly in the short-term. And on the demand side, only 25% of those eligible for vouchers receive them due to a lack of funding. Even those fortunate enough to receive a voucher often struggle to find a landlord willing to accept it.

The brutal truth: Without more supply, there are few ways to keep the needle from ticking up on the affordability front. There are only two options: Unlock existing supply, or bring additional housing stock online.

ADUs and tiny-homes can help. Vertically integrated developers such as Apt and Juno offer hope for a more affordable future for multi-family structures. On the single-family side, builders such as Welcome Homes and Homebound offer a lens into the future. But construction is expensive (and getting more costly, not less) and time-consuming. Thus, we must find ways to open existing supply.

ADUs and tiny-homes can help. Vertically integrated developers such as Apt and Juno offer hope for a more affordable future for multi-family structures. On the single-family side, builders such as Welcome Homes and Homebound offer a lens into the future. But construction is expensive (and getting more costly, not less) and time-consuming. Thus, we must find ways to open existing supply.

PadSplit

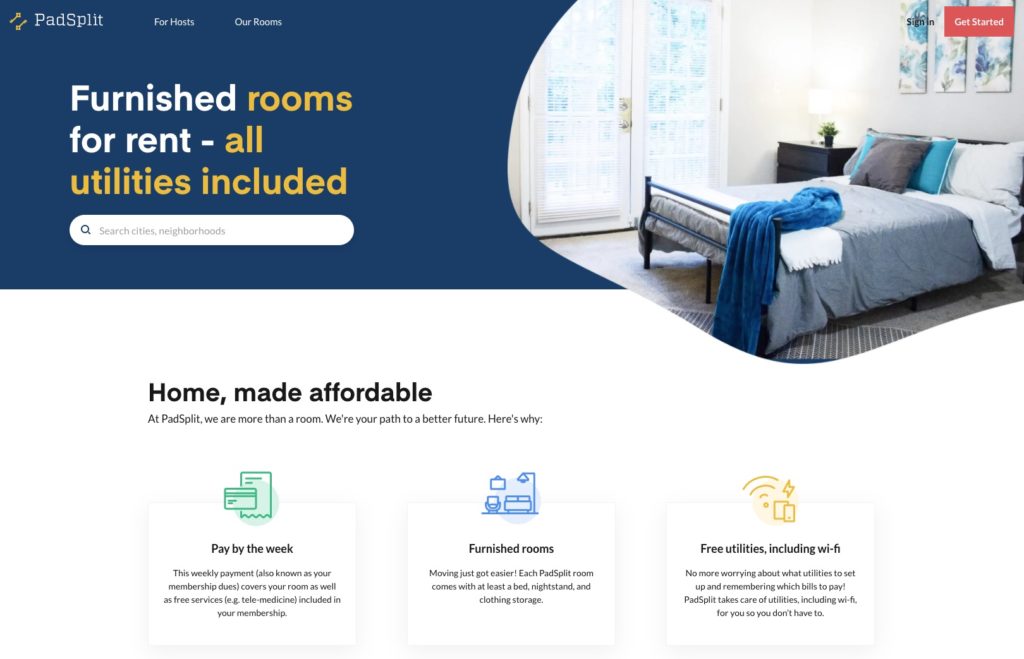

PadSplit is a marketplace for shared lower-cost housing that brings inventory online by creating co-living environments that are safe, attractive, respectable, and accessible to those who can only afford up to $750 per month in rent.

A few trends underlie its model: Bigger housing stock, smaller families, and flat incomes. The platform bridges the mismatch between those trends and balances them by putting more people into existing spaces.

It makes shared housing more profitable by making it more affordable. Rather than a landlord renting a 3-bedroom house for $1,750 to a family, the house is reconfigured into 5 bedrooms, each of which might rent for $500.

To date, PadSplit operates more than 1,600 units. It charges landlords a 12% recurring platform fee plus a 2.75% flat-rate transaction fee, for 14.75% total fees.

CEO Atticus LeBlanc elaborated to Crunchbase last year: “Room rates average $109 per week and include furniture, utilities, Wi-Fi, laundry, telemedicine visits and credit reporting for all on-time payments. Members are able to save $516 per month on average, enabling them to purchase their own vehicles, build credit histories, and ultimately move into their own apartments or homes.”

Compared to the $1,500 cost of a 1-bedroom Atlanta rental, according to Zumper, $436 per month for a room is beyond a steal for those without families.

PadSplit seems to successfully align incentives for single-family rental owners who want to improve the bottom line with those seeking affordable housing options.

Modernizing an industry that’s been around for generations, its mission is to solve the affordable housing crisis “one room at a time while leveraging housing as a vehicle for financial independence.” There’s nothing not to like about that.

And clearly this premise and business model resonate with real estate investors: It raised a $10 million Series A last August.

Note: This podcast with the founder is a good listen, and PadSplit’s Atticus LeBlanc was also interviewed by Robert Hahn, Lynette Keyowski, and Albert Hahn in Episode 4 of The Blueprint Sessions:

The Blueprint Sessions N. 4: Padsplit CEO Atticus LeBlanc

Atticus is the founder of PadSplit, Inc and co-founder of Stryant Investments, LLC, and Stryant Construction & Management. He has been an affordable housing advocate and investor since 2008, when he began acquiring distressed single-family homes in Southwest Atlanta. PadSplit was founded in 2017 after earning a grant from the Enterprise Community Foundation’s ATLChallenge affordable housing competition.

Broader Landscape

PadSplit is not a true novelty in the shared rooms space.

Craigslist is a big contender on the discovery side, as are platforms such as ShareRooms.com. More modern, vertically integrated approaches include Bungalow—which similarly repurposes assets but focuses on a more affluent audience and has raised $68 million—and Loftium, which I heard struggled during this past pandemic year due to its reliance on booking travelers into shared rooms, rather than renting entire homes (a segment that boomed).

Further, you can’t have this conversation without mentioning Airbnb, which got its start helping people rent spare rooms, couches, and even floors to strangers. Its origins are the very definition of shared living, though it’s obvious today its core business comes from renting entire homes, not bedrooms.

Communal Opportunity

Helping landlords place tenants more effectively is one monetization route. A follow-on opportunity exists–a SaaS offering to manage communes. Software can help add certainty, convenience, accountability, and credit building to the dated practice of communal living.

When people think of communes, they think of Kibbutzim in Israel and ashrams in India. And others think of “cults,” such as Jonestown, rather than communes.

Gillian Morris “use[s] ‘commune’ to describe a set of adults living together by choice rather than economic necessity, where any ‘profits’ made are shared by the community.” In that sense, the five-bedroom house I lived in for a year while working at Zillow was a commune, as was the three-bedroom apartment that five of my best friends cycled through over the course of four years. I’d also classify fraternities and sorority houses as communes. And, if you lump those two housing arrangements together … well, all of a sudden we’re talking about how a massive segment of the population lives in their late teens and twenties.

In every house, generally, one person serves as the house accountant and rule enforcer. Most of those groups of roommates aren’t willing to pay to find additional house mates, but I suspect would pay for a tool that eases their own workload (aka solves the manual mess).

I’m a huge believer in the power of shared living, both socially and economically. It’s the best of both worlds. An operating system for any shared single family residence with roommates is a product I’ve yet to see. In other words, PadSplit should launch the communeOS so that more people can experience the power of shared living—without one person having to shoulder the burden. Add a neighborhood layer such as Venn on top of that, and all of a sudden, you’re talking about a holistic community experience.

-Drew Meyers

The GEM: A private & paid community connecting the boldest entrepreneurs across every proptech sector, consisting of 400+ founders, execs, VCs, and practitioners. Discover an exclusive, objective lens into the trends, companies, people, and ideas shaping the future of real estate and the broader built world: Apply here.