I haven’t written in a while. Part of it is being extremely busy with work, which I hope to be able to tell you all about soon, but a big part of the reason is dread. I keep looking for white pill stories, visions of a bright future, or at least some kind of a hopeful analysis of what’s going on… and I keep failing. We are living through the ancient Chinese curse: interesting times indeed.

But I thought I would break my silence, at least to you all the VIP audience, by laying out what I’m seeing today. This is the result of a conversation I had a couple of days ago with a friend who is also a VIP subscriber. He asked if I would do a series on the changing housing market, on macroeconomics, on legal issues, and on the industry as we go through these unprecedented times. I told him why I was having issues being such a Debbie Downer when real estate brokers, agents, MLS executives, and tech company leaders are busy as hell trying to keep up with things. We had a great conversation, at the end of which he told me to write it up, because it might be dark, but it helped him think through his own company’s issues and strategies for the next couple of years.

So I’m doing that now.

I realize that I already have a bit of a rep as a Chicken Little doomsayer, so… if that isn’t what you’re in the mood for, please skip over this entire series. Chances are, I’m likely wrong, or the timing is off, and things will never be as bad as I fear. I’m not an economist, nor am I a Fed official, or a government policymaker or any such thing. I’m a strategy consultant who watches the real estate industry, and things connected to the industry. Feel free to ignore or dispute everything I’m laying out here.

.

. <insert Jeopardy music here>

.

Still reading? Still here? Okay, then I’ll assume you’re up for a trip down some dark pathways.

There are, I think, four major issues/trends that are confronting the real estate industry. At least three of them are not directly related to real estate, but because real estate and housing are such major parts of the economy and so deeply affected by macroeconomic policies, they will land on us first.

In this part 1 of this series, we’ll tackle the first horseman riding on a white horse: legal and regulatory disruption.

Legal and Regulatory Disruption

I’ve been writing about the commission lawsuits since two days after Moehrl v. NAR was filed. Since you’re VIP, you have likely read all of them. If not, I invite you to go back and re-read them. Start with this post from March of 2019:

I know I’m accused of hyperbole by some, but I really don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say that this case could be a nuclear bomb on the industry. If the court rules in favor of the plaintiffs here, REALTOR Associations evaporate, the MLS likely dies off, and the entire infrastructure of residential real estate in the United States has to be remade. It could be Ragnarok, the final end of the world battle of Norse mythology. Hence the title of the post: twilight of the Gods.

Over the last three years, it’s as if the industry has forgotten that this lawsuit was going on. Sure, COVID had something to do with that, but a lot of it comes from faith that NAR will emerge victorious. But recent setbacks, such as Burnett v. NAR (formerly called Sitzer v. NAR) getting certified as a class action lawsuit, the reversal by the 9th Circuit in the PLS v. NAR lawsuit, and the denial of the motion to dismiss in the Rex v. Zillow lawsuit, have started to get people’s attention.

I’ve written about all of these before, and I keep discussing them in presentations and podcasts and such, so I’ll invite you to go read the archives, listen to a few podcasts of mine both on Industry Relations and on Notorious POD and maybe attend an event I’m speaking at in the future.

Nonetheless, let’s spend a few minutes going through each of these things since I believe that the plaintiffs in all three are likely to win at least at the trial court level. Those will shake the industry in increasingly stronger waves.

REX v. Zillow

Let’s start with the least impactful lawsuit: REX v. Zillow.

This lawsuit will have relatively minimal impact, since the issue there is the antiquated self-protectionist no-commingling rules of the MLS. The basic rule is that some/many MLSs have rules that prohibit displaying listings that come from them with other listings from other sources. The restrictions at the heart of the lawsuit is the prohibition against mixing listings from the MLS with listings from non-MLS sources such as FSBO, new construction, and of course, non-MLS companies like REX.

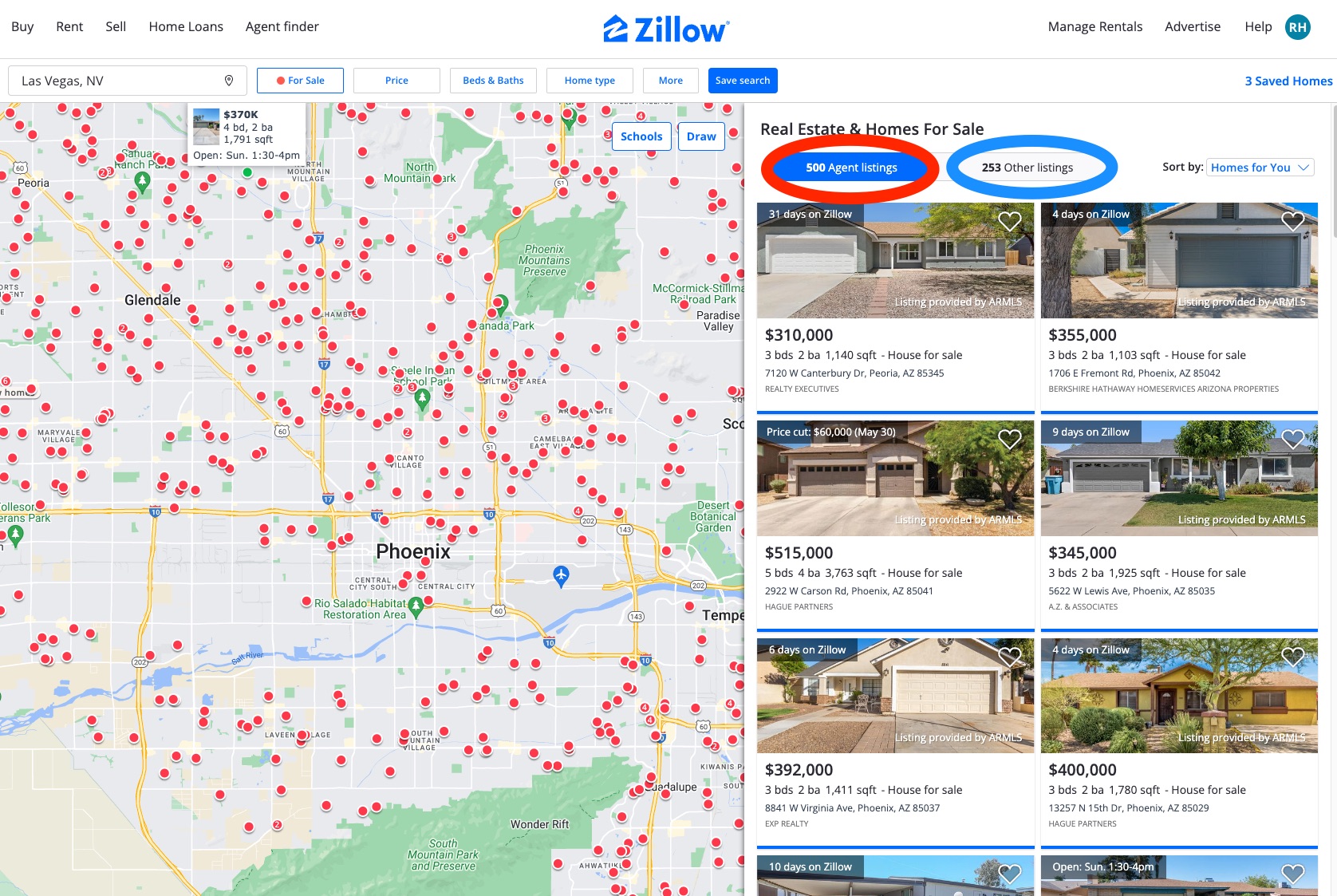

When Zillow became a brokerage and joined the MLS as a participant, it came under the rules of the MLS, most of which is set by NAR. Accordingly, Zillow separated MLS-originated listings from non-MLS listings into two tabs: Agent Listings and Other Listings.

Rex sued Zillow and NAR, among others, and lost its first big motion: a preliminary injunction. But then, it won on a motion to dismiss the lawsuit. What was striking about that is how the court did a complete 180 between the first ruling and the second, and I wrote about that at the time:

Things get interesting right off the bat. This same judge had denied REX’s preliminary injunction request because he had “conclud[ed] that Plaintiff failed to satisfy its burden to show a likelihood of prevailing on its federal and state law claims, or a likelihood of suffering irreparable harm in the absence of an injunction.”

So… if the judge thought REX was unlikely to prevail, then why deny the Motion to Dismiss? I know legally speaking that the issue isn’t simply whether the plaintiff is likely to prevail, but also whether there will be irreparable harm without the injunction. But… let’s just say that the tone of the judge’s writings is different.

Turns out, the reason may have to do with a certain federal agency whose name starts with “D” and ends with “epartment of Justice.”

I think what happened here is that the judge did the first opinion based on what he knew at that point, and then read up on Moehrl, Sitzer, Leeder, etc and the legal controversies surrounding real estate commissions, surrounding NAR, the MLS, etc. etc. and changed his perspective on the case in front of him.

A major influence, I think, might have been the intervention by the Department of Justice. We get this tantalizing reference in the second order:

Defendants now move to dismiss the claims asserted against them. NAR also requests that the Court take judicial notice of certain documents.

Plaintiff partially opposes the request with respect to two of the documents, a complaint filed in a civil case, and the final judgment entered in that case, including a 2008 consent decree between NAR and the United States.

The United States also filed a statement of interest asking this Court to decline to draw any inference in NAR’s favor from the 2008 consent decree, which is now expired. The Court previously noted the existence of that consent decree in ruling on the motion for a preliminary injunction. Because no one disputes the authenticity of these court records, the Court GRANTS NAR’s request to take judicial notice of them as well as the unopposed documents in ruling on the instant motions. [Line breaks added, citations removed, and emphasis added]

I infer that in the first opinion, the Court was in fact swayed by the 2008 consent decree that implied all sorts of pro-competitive benefits from the MLS. In this second opinion, with the DOJ literally telling the judge to ignore anything nice about the MLS or NAR that consent decree had to say, we get the opposite outcome.

I can easily imagine that the judge, or one of his clerks, picking up the phone when they get the unsolicited DOJ filing and asking, “Hey guys? What’s up with this?” and getting an education on where the DOJ and the FTC and the United States government (remember, the Biden Executive Order) stand vis-a-vis NAR, the MLS, and the real estate industry… of which Zillow is now very much a part.

In light of that change in tone and approach, I think REX is likely to win at trial. That victory will be a nice payday for REX and its investors, since the damages will be equal to whatever REX’s valuation was when investors put their millions in, plus whatever they can convince the judge REX would have been worth until NAR and Zillow drove it out of business. It’ll be an expensive judgment, but really, at the end of the day, the rule impacted is a relatively minor one that MLSs concerned with protecting their monopoly on listing data care about. Maybe some agents care, but really, Zillow was a one-tab affair for over a decade and it didn’t crush agents or anything. The no-commingling rule won’t be missed.

PLS v. NAR

Where REX v. Zillow is not particularly important, except as a sign of the DOJ’s hostility to all things NAR, PLS v. NAR will have a major impact. The rule at issue there is Clear Cooperation Policy. When PLS (Pocket Listing Service) wins at trial, and the court strikes down Clear Cooperation Policy as anticompetitive… that will result in significant chaos.

Since I’ve written and spoken about this rather extensively, let me summarize:

- Real estate agents have long wanted to do things like Coming Soon and exclusive listings and setup private networks for a variety of reasons. Some reasons were selfish (double end the deal, baby!) and others were not (don’t want to work with incompetent morons on the other side).

- When companies like Compass made Coming Soon and exclusive inventory a central plank of their strategy, NAR acted to eliminate the ability of brokers and agents to do anything outside of the MLS. Hence, Clear Cooperation Policy.

- PLS sued NAR for passing Clear Cooperation Policy, but the case was dismissed by the trial court. So much for that, said everyone. Other than PLS, that is, who appealed the decision to the 9th circuit.

- To NAR’s shock and horror, the 9th circuit reversed the lower court’s dismissal, and remanded the case back. But while they’re at it, the 9th Circuit made its views perfectly clear. I wrote about that here:

The 9th Circuit took the Defendants to the woodshed. I don’t think they needed to do that just to correct the trial court’s errors. That they did so suggests to me that the 9th Circuit has already made up its mind on Clear Cooperation Policy: it is, in their view, an anticompetitive violation, a group boycott intended to hurt competitors to the MLS. Knowing that, the trial court will act accordingly in the new remanded trial.

The fact that the 9th Circuit laid out all of the arguments of the Defendants, then dismantled them all one by one, effectively making the arguments for the PLS’s lawyers at the trial below is… well, significant. NAR and the defendant MLSs are going to have to come up with new arguments, or some new facts, if they’re going to prevail at trial. That is, to put it mildly, a tall order.

Which means that in all likelihood, they lose at trial. Appealing that decision to the 9th Circuit would be pointless, since we all know what the 9th Circuit thinks about CCP, about NAR, about the Defendant MLSs. Which means you appeal, go through that rigamarole, and then hope for Supreme Court to intervene. That’s not a happy scenario. Nor is it going to happen anytime before say… 2027? 2030?

The Demand for Pocket Listings

Even with the prohibition, off-MLS activity is as high as it’s ever been. Redfin’s study suggests as much and I wrote about that here:

And here’s Redfin updating the analysis in December of last year. That post notes how almost half of the real estate agents think pocket listings are more common now:

Redfin also provides some stats, showing that pocket listings and off-market activities are down slightly from earlier in the year, but up overall from 2020 and pre-pandemic levels:

In the third quarter, 2.3% of homes listed were marked sold or pending on the same day. That’s down from a peak of 3.2% at the start of 2021, but still higher than the 2.1% level we saw in the third quarter of 2020 and the 1.5% level in the third quarter of 2019. Redfin’s same-day sales data goes back to the first quarter of 2012.

…

The share of homes that sold without being listed on the MLS—another measure of potential pocket listings—also fell in the third quarter. It dropped to 21.4% from a peak of 23.9% at the start of the year. Still, that’s higher than the 20.4% level we saw in the third quarter of 2020 and the 21% level in the third quarter of 2019. Redfin’s off-MLS sales data goes back to the first quarter of 2012.

The shocker though is the Metro Level Summary that Redfin provides. I won’t embed the whole thing, so go read the post on Redfin’s blog. But some standouts:

- Allentown, PA: 1.3% Same Day Sold and 29.1% Never Listed. So almost a third of homes sold in Allentown were pocket listings.

- Birmingham, AL: 1.5% Same Day Sold and 26.5% Never Listed.

- Knoxville, TN: 0.8% Same Day Sold and 24.4% Never Listed

- Jacksonville, FL: 4.0% Same Day Sold and 20.3% Never Listed

This is happening with Clear Cooperation Policy in place. What will things look like without Clear Cooperation Policy?

What Is an MLS Without Listings?

The chaos will stem from the fact that agents, and particularly the top producing agent teams who all have buyer agents to feed, will look to do Coming Soon listings and other exclusive inventory strategies going forward. They’re already doing it, as the Redfin study shows; the court’s decision simply allows them to do it openly once again.

According to the Redfin study, almost a third of the sales in Knoxville, TN were Same Day or Never Listed. By implication, the Knoxville MLS (Knoxville Area Assoc. of REALTORS) has 66% of the listings in it for its agent subscribers.

What happens if those numbers flip? If 66% of the sales in Knoxville are Same Day or Never Listed, and the MLS only has 33% of the properties for sale in its system…what good is the Knoxville MLS then?

Yep, that will be chaos. Entire brokerage models collapse. The Association likely collapses. The MLS collapses. It’s the zombie apocalypse. And that’s from one small inside-baseball rule, because of market realities of dominant agent teams, super-pareto concentration of power in the top few agents, and existence of things like private networks (maybe PLS.com itself returns? Top Agent Network never went anywhere, after all) and even private Facebook Groups.

What’s truly damaging about PLS v. NAR is the fact that the 9th Circuit has already signaled its intent. If NAR loses, then it had best go direct to the Supreme Court and pray for certiorari.

The Commission Lawsuits: Burnett v. NAR and Moehrl v. NAR

The big daddy of course, is Burnett v. NAR, which seeks to eliminate the sharing of commissions between the listing agent and the buyer agent. I further believe that the Moehrl v. NAR lawsuit going on in Illinois is likely to get consolidated with the Burnett case in Missouri. (If you’re interested, read up on Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation in this law review article.) The issues are the same, the arguments are the same, and the defendants are largely the same. Knowing that, it is quite likely in my view that plaintiff’s firms will file copycat lawsuits in all 50 states, in all 12 federal circuits, with the hope that their lawsuits will also be consolidated into the coming one mega real estate antitrust lawsuit.

I won’t go deep into this one because I’ve written about it over and over again, and talked about it over and over again. But once again, summary:

- Plaintiffs are alleging that sellers paying the buyer agent leads to high commissions.

- The theory is that buyer agents steer their clients away from homes that don’t offer high compensation.

- The entire case, in my view, hangs on whether plaintiffs can prove that steering happens all the time or defendants can prove that steering is a tiny problem that is already against the Code of Ethics and state fiduciary agency laws.

REALTORS bitching and complaining on Facebook, or in the comments section of this blog, are completely missing the point. You are not the attorney making arguments in front of the court. You pointing out this reality or that, saying how lawyers are stupid and judges are morons, or how this is communism come to America do nothing to affect the outcome of the case.

As bystanders who aren’t arguing in court, the only issue we have to deal with is, “What happens when the plaintiffs win?”

The money damages alone would bankrupt every single REALTOR organization, every MLS, and all major brokerages. Put it this way: many calculate that annual real estate commissions in the U.S. averages about $60 billion a year. Knock estimated that 2020 commissions were about $90 billion. The plaintiffs in Burnett v. NAR was asking for class action status from 2015. So that’s 7 years, times $30 billion (half of the commissions paid to buyer agents), and treble damages as provided for in Sherman Antitrust act… $210 billion in damages. Nobody is paying that. No insurance company is paying that. So say it’s reduced to 10% of that figure, or $21 billion. Everybody is still bankrupt the next day.

Not to mention, an injunction against commission sharing fundamentally changes how business has been done in the U.S. for over a century. Residential real estate looks like commercial real estate then. Once again, I’ve written about this and spoken about this but here’s a summary of my take on what happens after this bomb drops:

- Buyer commissions go away, because it doesn’t make any sense to pay a buyer’s agent a percentage of the sale price. If anything, buyers would want to reward their rep for saving them money, not costing them more.

- Perhaps more buyers go unrepresented, but I think most buyers will move to a flat fee or hourly compensation arrangement, as they do with lawyers, accountants, and even doctors.

- Listing agents will still be paid via commission, since it makes sense to incentivize salespeople to try to get the highest price possible.

- However, competition between listing agents and listing brokers will lead to the listing commission dropping from the “customary” 3% (2.5% in many markets) to perhaps more like 1.5% or so. I base that 1.5% number on what Redfin charges to list a home, and Redfin is a full-service brokerage.

- Every brokerage in the United States is in instant peril, as half or more of their revenues come from buy-side commissions, and that’s going away.

- Zillow is in deep trouble, as its Premier Agent program is primarily a buy-side leads referral program. If buyer leads are worthless (or at the very least, worth less than before), then Zillow’s revenues plummet. This is especially true if Zillow has put most of the Premier Agents on Flex, which is a 35% referral fee. 35% of a $15,000 commission is a very nice payday; 35% of $25/hour for four hours is not.

- Repeat the above observation re: Zillow for every company dependent on buy-side commission referrals, such as Realtor.com and various other lead-gen platforms.

There are other consequences of residential real estate looking like commercial real estate, but read my other works for details on that.

Suffice to say that Burnett/Moehrl is a nuclear bomb on the industry. I called it Gotterdammerung, or Twilight of the Gods, because it really would be that serious for real estate as we know it.

As an aside, because it’s fresh on my mind, have you ever read through the Rules and Policies of your local MLS? The one I just reviewed is over 150 pages long. I would estimate that at least 100 pages become irrelevant if cooperation and compensation go away. It isn’t clear to me at all how the MLS has any rules or enforces any rules without compensation. Perhaps more on that in a future post or podcast.

The United States v. NAR

Finally, we should touch on the fact that the United States sued NAR, but filed a settlement on the same day, and then walked away from the settlement once the new administration came into power. That the DOJ has never ever done this in its entire history should not be lost on anybody. The career enforcers at the DOJ think that real estate is plagued with anticompetitive practices, and believe that NAR is a bad actor who needs to be brought to heel. It doesn’t much matter if we disagree, if we think the DOJ is filled with elitist idiots, or whatever; what matters is what they believe and what will happen.

Before, during and after walking away from the settlement, the DOJ had intervened in a number of lawsuits against NAR, such as REX and PLS and others. DOJ did this without anybody asking for their opinion. It should be clear to anybody paying attention that the United States is waging warfare against NAR.

Now, normally, when a company is told to jump by the DOJ, said company’s response is, “How high?” Compliance is expected and demanded. When the DOJ has to actually bring lawsuits, it annoys them. So what happens when the company not only pushes back, but brings a lawsuit against the DOJ? I have no idea, but let’s just say that I went to law school with a number of people who became regulators. They’re going to take shit personal-like when things get like that.

I’ve already written on the subject of NAR’s lawsuit against the DOJ. From where I sit, this is a no-win situation for NAR. Even if they win, they lose:

If NAR wins, things get more interesting. Because victory means that the DOJ can’t investigate further. The Court will enjoin the DOJ and quash the CID. I imagine the DOJ will appeal, since they have an unlimited budget, but let’s say that the DOJ is forestalled for now.

Does that stop the FTC? After all, I’ve already written that the big guns for the United States in this is not litigation through the DOJ but regulation through the FTC. And I wrote that before the Biden Executive Order directing the FTC to do just that: regulate real estate brokerage and listings.

Presumably, the FTC will undertake its own broad investigations and issue its own CIDs to NAR and others. If the Court prohibits the DOJ from investigating NAR’s Participation Rule, does that prohibit the FTC from investigating it?

Plus, it isn’t as if the NAR-DOJ agreement binds the various state attorneys general:

Suppose that the court order does somehow stop the FTC. Does that stop non-federal investigations? I can’t imagine that it would.

So if the absolutely livid DOJ and FTC decide to go after NAR anyhow, and the court order stops them from investigating NAR, what stops them from providing large block grants in the tens of millions to state attorneys general so they can start peppering NAR with all kinds of investigative demands that look exactly like CID 30729?

Sometimes, discretion is the better part of valor. There are fights to fight, and then there are pyrrhic victories where you can’t afford to win.

So the DOJ has likely sharpened its knives for NAR and all things REALTOR, but that’s less of a threat than you imagine, because….

The Real Action is Regulatory

Thing is, I’m not overly concerned about these lawsuits. I’m not worried about the courts. Lawsuits take years and years and years. I think we have at least 5-7 years before a final resolution of these mega lawsuits is reached, and I think there will be some sort of legislative/government intervention to save the real estate industry from certain doom. If the government was willing to step in to save Big Tobacco, I think it will step in to save Big Real Estate.

The real action is not lawsuits coming from the DOJ, but regulations coming from the FTC. I wrote about that in this post:

For the TL;DR crowd: I think the real action in terms of achieving the goals of the government is in regulation, not in litigation. That means the DOJ will do its thing through the courts, but the main impact is likely to be the “broader investigation” that it has promised, which will lead to other agencies (I think the Federal Trade Commission is most likely) actually doing the heavy lifting through regulation of the industry.

Mere days after that post, President Biden drops his Executive Order on Competition. Buried in that Executive Order in Section (5)(h), which pretty much the entire corporate media failed to notice, was this:

(h) To address persistent and recurrent practices that inhibit competition, the Chair of the FTC, in the Chair’s discretion, is also encouraged to consider working with the rest of the Commission to exercise the FTC’s statutory rulemaking authority, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, in areas such as:

…

(v) unfair occupational licensing restrictions;

(vi) unfair tying practices or exclusionary practices in the brokerage or listing of real estate; and

(vii) any other unfair industry-specific practices that substantially inhibit competition.

This is not a request. This is not a letter from a couple of senators asking the FTC to do a study. This is an order from the President, to whom the Chair of the FTC reports. The language about “encouraged to consider” and “in the Chair’s discretion” is, I think, standard CYA smokescreen. The FTC will rev up their engines… especially since the FTC and the DOJ are kind of like two sides of the same coin.

So whatever happens with the Burnett/Moehrl/MegaAntiTrust lawsuits, I think the FTC will hand down some pretty significant regulations in the not too distant future.

Why Regulation? Why Now?

First, the initiative is different in regulatory action vs. litigation.

Say the DOJ brings a new lawsuit against NAR. That goes to court. Years of motion practice, of discovery, of investigations, etc. pass. The DOJ wins. NAR appeals. We go through a few more years of litigation. DOJ wins the appeal. NAR files for certiorari with the Supreme Court. Years pass.

Meanwhile, business continues as usual.

If, on the other hand, the FTC promulgates a regulation, then NAR has to sue the FTC to stop that regulation from going into effect. Courts don’t like to grant preliminary injunctions, never mind preliminary injunctions against the federal government. The burden of proof shifts to NAR in that scenario. NAR sues, and wins. FTC appeals. NAR wins at appellate level. FTC appeals up to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the regulation remains in place.

This is kind of what happened with the CFPB, when it promulgated regulations on mortgage banking and started to fine companies and sue them for various alleged infractions. Quite a few companies just settled, like Nationstar settling for $91 million rather than going to war against the CFPB.

Second, with lawsuits, it is ultimately the court who decides what to do. We don’t know what the courts in Burnett v. NAR and Moehrl v. NAR will order, even if the plaintiffs win. Maybe the court just awards money damages, but refuses to enjoin the practice of compensation: sellers paying the buyer agent. Maybe the court just strikes down various mandatory NAR rules, but allows voluntary cooperation and compensation to continue.

With regulation, the FTC decides what the remedy will be, and then NAR will have to bring a challenge to the remedy. So we go back to the initiative thing above. When you look at the scope of the kinds of things that the DOJ wanted to investigate, it is apparent that the ideal “solution” for the government is the kind of intrusive regulation they’re so fond of, rather than legal judgments that tend to be not as finely tuned.

Third, why now. We’ll cover this in greater detail in a future part, as it has to do with politics. But let’s just say that 2022 is a midterm election year, and 2024 is the next presidential election. Housing has become, is today, and will be tomorrow a major political issue. The Democrats in power today would like to continue to remain in power; the Republicans would like to take back power. For both of them, going to voters with at least the appearance of having done something to “fix the broken housing market” will be an important political point.

Litigation can’t work on a schedule; the courts don’t much care when elections are. (At least, they’re not supposed to care.) Regulations can. The FTC can issue a few regulations in 2022 to help Democrats in midterms claim to be doing something to solve the housing problem, and then issue a bigger set of regulations in late 2023 or early 2024 to help President Biden with his reelection campaign.

Wrapping Up, With a Note on Politics

Let’s wrap up this first part. Everything has to be in pieces, because the whole fabric makes a lot more sense. But let’s leave this part one with a bit of a looking ahead to why things might be different this time.

Normally, NAR is one of the most powerful lobbying organizations in the country. As NAR’s old chief lobbyist once told me, when he leaves a message, senators call back. But housing politics in 2022 are very, very different for reasons we’ll explore in a future part. I don’t know that all of NAR’s money and PAC spending and influence on the Hill and with the agencies will make as big of a difference this time around.

I still do think that the government will organize some kind of a settlement scheme to ensure that NAR and the various real estate companies do not end up bankrupt overnight when the commission lawsuit damages come in. I don’t know that the government will actually pass legislation to enshrine NAR’s priorities, like cooperation and compensation, 1099 independent contractor status, and Clear Cooperation Policy. The politics are too different now.

Let’s leave it there. In part 2, we tackle the second horseman: inflation and the housing market.

-rsh

The Doors – Riders On The Storm 1971 | Unofficial Music Video

It was not my intention to make this video, I already created an ‘Riders on the Storm’ video on the Vietnam War. However, when I saw the new official video of this song I couldn’t resist. I respect the creators their vision, but I think most of us agree that it doesn’t got the soul of the Doors.

“… going to voters with at least the appearance of having done something to “fix the broken housing market” will be an important political point.”

The quickest way to get the melt-up under control is to tell every buyer in America that they will have to pay their agent 3% out of pocket. Sooner or later (if it hasn’t already happened), the lizards will stumble upon this revelation.